Until India, I have never been so encaptured by a culture that I didn’t want to leave it. The food is probably the best in world with so much variety and flavor on both sweet and savory spectrums.

The people typically kind, prideful, eager to engage and helpful (if it’s not their job to be so). The colors make the rest of the world seem bland. Saris always shouting brightly with shimmering patterns. Intricate, unique artwork can be found everywhere in monuments, crafts and even ordinary street art windows.

Even the transportation trucks, lowered to basic standardization in the West, sport custom paint jobs and ornamentation! Yet, India is a complex county and sometimes hard to understand. I want to share several themes I’ve come to love from this magical place.

India’s Coexistence of Competing Ideas

After six weeks, I found myself both in love with and frustrated by India. No other reaction seems more fitting and natural. India itself contains this duality that I have come to describe as a coexistence of competing ideas. In Shantaram, the author calls this the law of necessity.

This theme runs through all life here but is best demonstrated through the idea of helpfulness. I have been helped in so many ways by new friends I’ve made in India that would be considered going out of your way in the West. It is the communal culture to do so by helping me get to a doctor without queuing, accompanying me to pick out clothes for an Indian wedding or calling customer service and then escorting me to a store to figure out why my SIM isn’t working. Things happen in India through personal connections or you face the painful… strain… of getting things done through the ever-present bureaucracy as a fumbling, unknowing foreigner.

For these people whose job it is to help you (hotel staff, customer service, people who answer phones, store staff, etc.), they seem to desire only doing the minimal amount of work to make you go away. In contrast to personal friends going out of their way, customer service people in no way will creatively solve your problem outside of an existing rule book.

I’ve been told to “look on the internet” when enquiring hotel staff about buses, asked “why don’t you do it yourself” when trying to change hotel dates, and told “please call back later” when a hospital staff don’t understand my English when trying to schedule a vaccine administration. Any promise that something will be achieved outside of the present moment or field of vision is unlikely to happen. As evidence by both times Sadie and I bought prepaid SIMs that not only activated after the time specified (8-24 hrs) but when activated each time required some effort to get charged with our purchased prepaid plans.

I wanted to at least mention though that we had several hotel staff who were incredibly caring and kind at all ends of the payment spectrum. A review above 9.0 on booking.com will surface these people.

The Universal Value of Life

This duality also shows up in one of the things I love most about Indians: their value of all life. Probably most expressed in a conversation with the host of my home stay in Agra. Looking over a dirt field from my home stay’s roof, he was describing how everything was connected and referenced how he provides a bowl of water for the birds on this roof. Next he pointed to some ant hills in the dirt lot below. He told me some people will show up and dip long sticks into those anthills to give the ants food and make sure they don’t starve. I had personally seen people regularly feed birds in plazas, observed jackets on street dogs, watched fires lit for street cows when it was cold and know of a temple where people provide for thousands of rats. It’s clear that the influence of Hinduism and Buddhism extended far beyond vegetarianism into everyday culture.

Some of these examples can seem ludicrous from the Western standpoint where we only take care of what is ours. Surely ludicrous to anyone who grew up in the Midwest constantly fighting to kill, trap and discourage invading ants, mice, squirrels and other animals. I still am bewildered by the ants example shared by my host. Even though I believe his honesty, I still have a hard time believing myself.

This respect for life flourishes in how Indians view coexistence with all beings. India is famous for the wandering street cows which graze not just in foreigners giving them roti but mostly on garbage. It can be bizarre that a sacred animal eats what you throw out in the trash but that is coexistence of culture and practicality India is also famous for.

Outside of Delhi, Tuk tuk, motorbike and foot traffic share the street with sauntering cows, sunbathing dogs, munching goats wearing light sweaters and pigs roaming the occasional trash area. Instead of placing things in a box all these things exist together. Yet to make this coexistence happen the practicality is that humans can not always yield to animal rights. Dogs growling at foreigners and cows trying to steal a meal from a produce stand are threatened with wood sticks. Certainly most dogs look at me as worried as I do at them when we cross within inches of each other. So respect for life and coexistence reach some limit where the people enforce rules using violence. This grey area, Indian’s own Yin and Yang, allows existence of higher morals and practical practices.

Honk if You Value My Life

Nowhere is that more present than the state of roadways, alleys, pedestrian paths or any drivable surface not protected by an officer with a stick. If a vehicle can make it through the tinniest alley sporting foot traffic, it will force its way through. Horn blaring all the distance. This practice somehow hasn’t deafened the entire population of India but it has probably saved millions of human and animal lives.

In India the horn is a life saving tool (rarely used in anger) in traffic-ways where the only rules are to minimize life loss, property damage and the amount of space between vehicles. Given the value of coexistence, everything is allowed on a road. Men pulling carts, stationary cows staring blankly into passing traffic, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, cars and whatever else that needs to move from in place to another. No one gets angry some entity is in their way, they just swerve around it while honking to let the slower entity know to not cross their path. Lanes get in the way of that but I think maybe Indians should rethink their flexibility with going the wrong way against oncoming traffic.

When pedestrians enter this madness we too behave like vehicles crossing the street through whatever space can be found with the acknowledgement that people will try not to hit us while driving as fast as they can around us. All this noise of passing vehicles can make walking the cities quite tiring as you wonder why your ears are not yet bleeding from the horn coming up the three foot pedestrian alley behind you and how you are alive after crossing 8 lines of traffic. However, I actually like the idea of their traffic allowing anyone to drive as they like and just trying to make sure people know you are coming their way. I haven’t seen any roadkill in six weeks despite the added obstacles huge stationary cows, running dogs and whatever else wanders into the road.

Ritualization Doesn’t Require Obedience

Finally, the last Ying and Yang example of India comes from Hinduism. Shrines big and small are all over Indian cities. They are really wonderful places where all the attending caretakers ask is for you to leave your shoes at the entrance and try to be quiet.

As a foreigner, a non Hindu, I never felt unwelcome at a location except from my own initial timidness not to offend. I don’t think I ever heard a babbling kid “shhhhh’d” like you might hear in a Christian church where you must show your obedience in one way or another. The duality here comes in flexibility of the rule of quiet. Quiet is respectful and reverent but it makes more sense to be inviting then it does to be hard and fast to some absolute rule. Hinduism and other “eastern religions” are very “come as you are”. Your practice, your ritual is very personal and I always felt so at home and peaceful sitting in or walking around these shrines for up to an hour.

Around the large Golden Temple complex (the highest significant site for Sikhs) people are conversing, kids are laughing, people are asking to take selfies with me, others are sitting off to the side chanting with the mantras played over loud speakers and a few bathing in the water surrounding the temple. Indians don’t need complete silence to practice or pay tribute to their religion. Their religion is intermeshed joyfully into their lives.

In a final example, I started my visit to India being engulfed in the wonderful commotion of attending a ‘short’ three day wedding of two my good friends. The contrast with Christian traditions was indeed laughable. During the “engagement” ceremony, where the woman’s family accepts the man’s proposal, people were eating, drinking and talking while on a little platform several people were involved in an intricate ceremony. Similarly, on the final night, the actual wedding ceremony came last, after what we would typically call “the reception” in the USA! At past midnight, when the ceremony started, only a couple dozen close friends and family remained after a feast involving a couple hundred. I barely made it the three hours later when the bride and groom walked around the fire seven times to actualize the marriage. Even at this final ceremony people were standing up, walking around, talking quietly and eating. Nothing of the serenity of silence demanded in the West.

Finding Privacy in a Land of Billions

All this coexistence I talk about is beautiful but also is a necessary part of life in a land containing 17% of the worlds population. Shantaran comments that if that many English, French or other westerners were crammed into a similarly tight space there would be a lot more ill will, grudges and violence. However, India was a very safe place and the people very joyful. I think Indians are used to a lot less personal space for this reason, especially talented considering their enthusiastic personalities and expressive conversations.

This lack of privacy was mainly us trying to grab some respite from the good will of the populous. Sitting alone seems to be a foreign concept and people have no problem standing by you, staring at you, trying to sell you something, begging, asking for a selfie or starting up a conversation. In Amritsar, at the Golden Temple, I finally become so frequently molested to take selfies with people as a tall, bearded gora sporting sunglasses while wearing a North Indian kurta and my long hair in a bun; that I started saying no to people. Many people will interrupt my conversation to ask. One person sat next to me and tried to take his picture with me after I declined. “This must be what it’s like to get no privacy as a celebrity. You want to hide”, Sadie told me after our day of being asked for a selfie a couple dozen times.

Walking down the street people frequently want to start up a conversation. Cries of “hello, sir?”, “excuse me”, “where are you from?”, “are you looking for something?”,

etc. follow me down the street. Most just to sell me something (eventually if not initially) but many are curious and proud hosts for travelers to their country. I took a lot of these conversations: had chai with a shopkeeper, met a Sikh software developer, helped write some English for a Tibetan buddhist in Facebook messenger and was invited to many peoples homes. However, sometimes I just want to take things in, not engage and be, me. This outward friendliness is a bit different if you are a women traveler but I get into that elsewhere.

The best example of this lack of privacy is when Sadie and I were trying to have a very important and personal conversation after checking out of our hotel room. Ten seconds after we found a bench away from the crowds in the Jaisalmer Fort (typically hard enough in itself) three kids came up to ask us our names, where we were from and if we had anything for them. Luckily the oldest girl (10?) spoke conversational English and took pity on our request for privacy. She hen corralled the other kids to her home 20 ft away where they just watched. However, every five minutes they or some other kid would wander over and speak the few English phrases they knew. Then of course there was the irregular pounding of some home or alley improvement going on. Imagine trying to have a meaningful conversation with your partner in these circumstances. Where could we go? We had no hotel room any more and our only other semi-private space was a small hotel common area.

So we continued on and actually had a break of 20 minutes where the kids finally got bored of us until a new group of 2 and then growing to 6 boys found us. They demanded to practice repeatedly their few English phrases on us to their enjoyment. Telling them no, stop and leave me alone in both English and Hindi initially abated their interruptions to every couple minutes until it began to fuel them into essentially shouting their, “hello. What it your name? Where are you from?” phrases at us continually so we had to give up and attempt to find a stopping point for our conversation while walking off towards street venders sure to call out the same questions.

Sometimes you don’t have a room for privacy, some times you do. However, that doesn’t stop most Indian hotel staff. They incessantly knock on our door to let us know or ask one thing or another. It’s like 3-4 interruptions on average. When you open the door, the frame is like no barrier and they happily walk right in. Maybe the historically cultural tabu of nakedness means people would never open the door if anyone wasn’t fully clothed. I don’t know but they don’t wait at the door frame.

The Indian hotel staff wait only a little bit longer between knocks than the breathes they take between their talentedly fast speech. If someone decides to knock at midnight it’s a race to get my clothes on and one time a fight to physically impose myself in the doorway against the staff asking and essentially physically wedging themselves through the crack I had opened in the door to grab an electric heater from my room for some reason we didn’t share enough common words to explain. I mean, that was a rare exception but another time at our home stay one of the family came right in and sat on a chair to talk to us while laying on the bed (fully clothed, just resting a moment). However, that conversation turned out to be very enjoyable and we became friends.

Yet is an example of how the door frame does have little power in India.

Lack of privacy in India is one of those redeeming things however that opens us up a lot more easily to meet, understand and befriend locals. I can say that the positives of it make me feel a lot more welcomed and communally taken care of than maybe anywhere else. The negatives are something we just typically we need a break to recover from due to differences in culture. Really, we are mostly just recovering from people being so outgoingingly interested in us with positive intent. So it’s not too negative a thing to recover from, outside the incessant goods hawking of course.

India is Hard to Leave

“I love India and it frustrates me” is my mantra about India. The flavor in color, food and music make most of the West seem pretty boring.

The peacefulness, openness and energy lure me in and make me feel a part of the society. The thousands of years of history and proliferation of art in both fantastic monumental buildings and ordinary house windows or transportation trucks is endearing

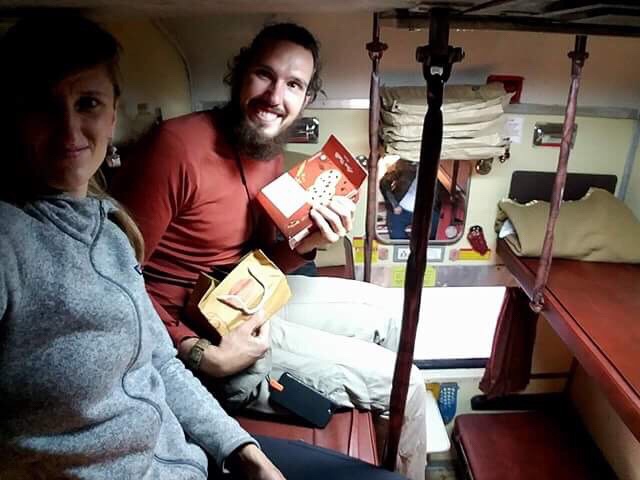

Yet, it has its own challenges like regulations that make it hard impossible to use foreign credit cards online or in person when nearly everything is online. Trains and busses seem to have an obligation to be two hours minimum late and up to 24 hours. People start negotiation for things at 10x the actual local price making it impossible to know what I should be paying. It takes practice to essentially offer to pay $5 when someone says something costs $500. It can be impossible to get privacy outside and sometimes even inside a hotel room. Finally, the constant horn noise both near and far from my ears and commotion (some would say chaos) can be unrelenting and get very tiring.

For every reason India is hard, it seems to redeem itself in the same moment. This is the reason you talk to people who plan on staying six months and now have been here 14. I was only planning to stay four weeks and ended up staying six while considering extending much longer. Part of the reason is that in a country as large as the United States each Indian provence has its own completely unique language, style, attractions and interests. Another part is how affordable the country is. Getting ripped off really bad probably only means paying $5 USD instead of $2 USD.

More than just being a lookie-lou tourist taking selfies in front of the Taj Mahal (although I did that), I learned a lot from how people treat each other, their environment and their religion. I am definitely better for this experience in many more ways than my improved ability to read an Indian menu. I hope to take the best I’ve seen here and bring it with me as I leave and continue so when I return. Good night India, good night.